By Merv Moore

Sports Director & Head Baseball Coach

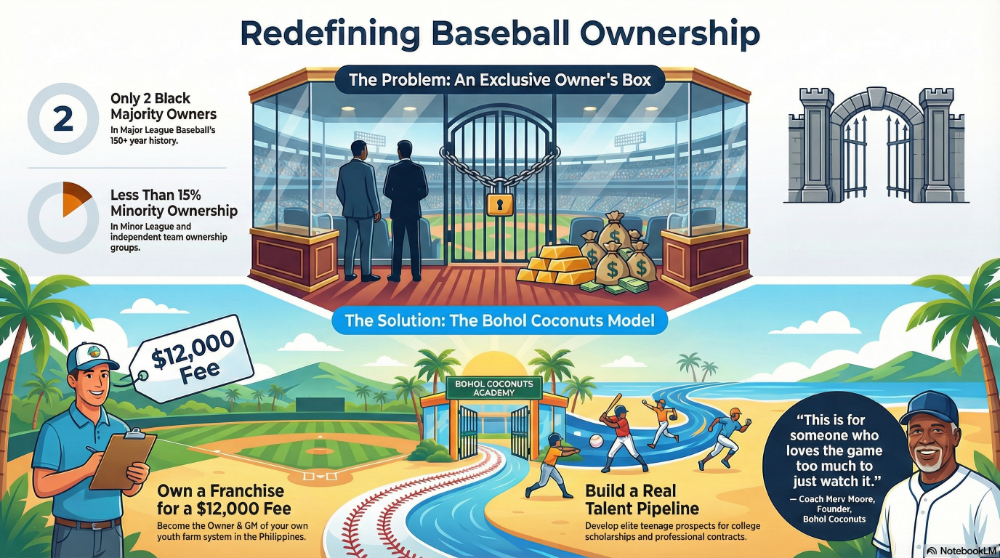

When Major League Baseball touts itself as a global game — citing the international flair of the World Baseball Classic, expanding broadcasts across continents, and scouting “the next great talent” from six continents — it’s easy to overlook the elephant in the room: the sport’s financial and developmental infrastructure remains overwhelmingly concentrated in the Caribbean and Latin America, while Asia — home to over 4.7 billion people and deep baseball traditions in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan — receives only a fraction of comparable attention.

The numbers tell a sobering story.

💰 Academy & Scouting Budgets: A Tale of Two Continents

MLB teams collectively spend an estimated $100–150 million annually on operations in the Dominican Republic alone — funding over 40 academies that house, train, and develop hundreds of teenage prospects year-round.

Sponsored Links

These academies employ full-time staff: coaches, nutritionists, language instructors, and medical personnel. Players as young as 16 live on-site, receiving structured training, English classes, and competitive game schedules — all at the club’s expense.

In contrast, MLB’s combined scouting and development budget for all of Asia — including Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and emerging markets like the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia — is estimated to be well under $15 million per year.

There are no MLB-owned, full-service academies in mainland Asia. Scouting is often handled by part-time regional coordinators or shared among clubs, and player development for non-Japanese/Korean draftees remains ad hoc, reactive, and under-resourced.

Japan and South Korea have strong domestic leagues (NPB and KBO), and players like Shohei Ohtani or Ha-seong Kim arrive in MLB after years of elite professional development — not via the amateur pathway MLB cultivates elsewhere.

For players from other Asian nations — especially Southeast Asia — there is no farm-system-style pipeline, no “single-A” tier, no “Coconuts All-Star Program” equivalent to prepare them for the physical, linguistic, and mental demands of affiliated ball.

📊 Opening Day 2025 Rosters: The Representation Gap

On Opening Day 2025, MLB rosters featured:

- 253 players born in Latin America or the Caribbean (including 112 from the Dominican Republic alone)

- 27 players born in Asia

- 12 from Japan

- 8 from South Korea

- 5 from Taiwan

- 2 from other Asian countries (1 from China, 1 from the Philippines)

Note: The sole Filipino-born player, a utility infielder on a National League club, was raised in California and drafted out of a U.S. college — illustrating the “gap” for homegrown Asian talent.

That’s a ratio of nearly 10:1 in favor of Latin American-born players — despite Asia’s population being nearly three times larger than Latin America’s.

🌏 Why This Matters: Toward a Truly Global Game

MLB’s current model isn’t global — it’s selectively international. The league has built a robust, vertically integrated talent pipeline in the Dominican Republic (and to a lesser extent, Venezuela), where early investment yields outsized returns: over 40% of MLB players are now internationally born, and the majority hail from the DR.

But replicating that system in Asia — especially in emerging baseball markets like the Philippines, Indonesia, or Vietnam — would require long-term vision, upfront capital, and humility. It would mean:

- Establishing regional academies (even shared, league-run facilities)

- Investing in youth infrastructure: bats, balls, fields, coach education

- Creating developmental leagues with wood or composite-wood bats to bridge the gap between amateur and pro play

- Launching inclusive scouting networks, not just chasing “finished” stars from NPB or KBO

The irony is palpable: while MLB seeks new revenue streams in Asia — from Tokyo Series games to jersey sales — it continues to treat the continent as a marketplace, not a talent pool. Compare that to the DR, where MLB sees children with gloves and dreams — and builds systems to turn them into All-Stars.

🌴 A Local Perspective: The Bohol Model

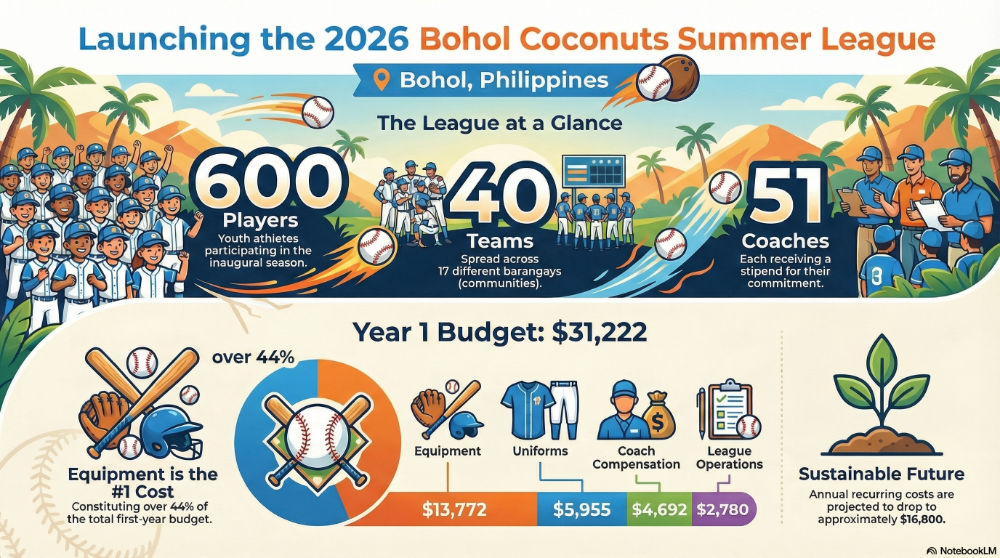

Here in Baclayon, Bohol, we’re piloting a scaled-down version of what could work across Southeast Asia: a farm-system-style youth structure with composite-wood bats, coach caps and stipends, barangay-based team limits, and even plastic-wiffle ball training for accessibility.

Sponsored Links

If MLB is serious about becoming a world sport — not just a U.S.-centric league with international flavor — it must match its rhetoric with resources. Until then, the “World” in World Series will remain aspirational — not actual.

Photo: All-Pro Reels | CC BY-SA 2.0

Marvin “Merv” Moore is the head coach of the Bohol Coconuts Baseball and Softball Club. He has coached in both Europe and Asia, and was a founder of both the international baseball websites, Mister-Baseball and BaseballdeWorld.